Breathe

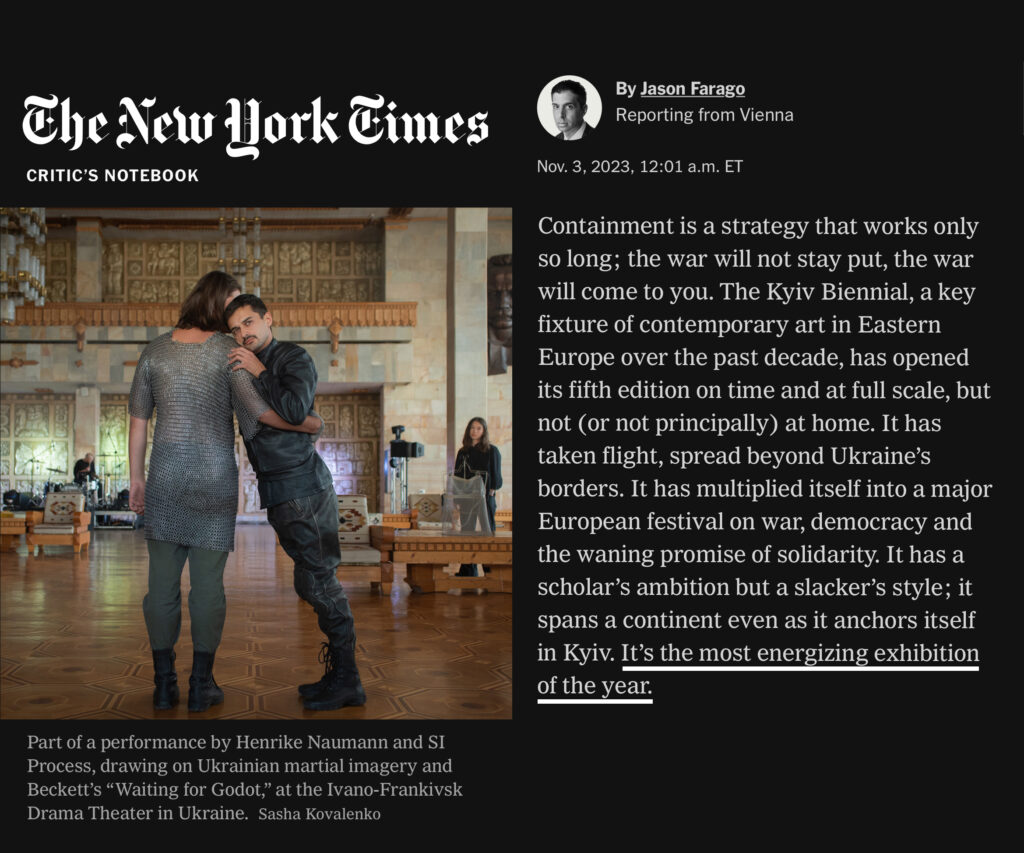

Kyiv Biennial 2023

Drama Theater Ivano-Frankivsk, Ukraine

Press

New York Times on the Kyiv Biennial

„the most energizing exhibizion of the year“

Süddeutsche Zeitung zur Kyiv Biennale

„Ausstellung des Jahres“

Monopol Top 100

22 – Henrike Naumann

RBB Kultur – Das Gespräch

Henrike Naumann – Kunst in konfliktreichen Zeiten

Infos

Drum machine man – SI_Process

Volodymyr – Viktor Abramiyk

Estragon – Oleg Panas

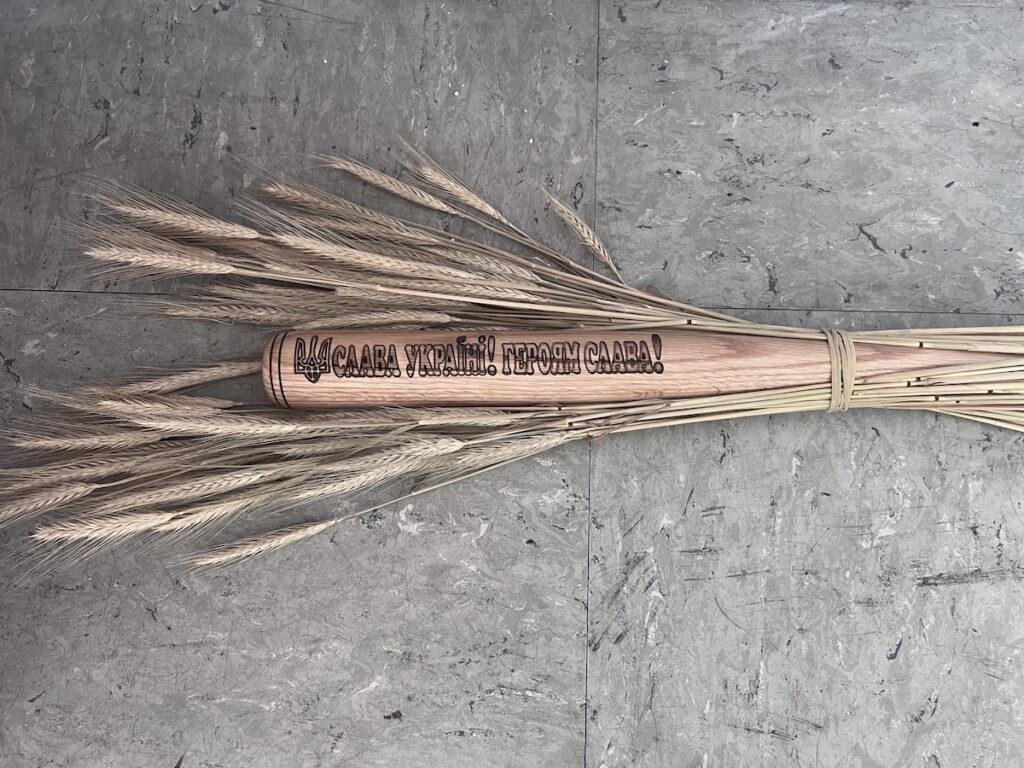

Special objects – Counterfuture

Special thanks – Olga Diatel, Illia Ruzumeiko, Andrii Sokolov and the whole team of Ivano-Frankivsk Drama Theater

7. Oktober 2023, 15.00

Drama Theater

Ivano–Frankivsk, Ukraine

Infos

Kyiv Biennial 2023

On the Periphery of War – Ivano-Frankivsk

Kuratiert von Alona Karavai, Roman Khimei, Yarema Malashchuk, Anton Usanov

Against the Logic of War – Kyiv Biennial 2023

“Breathe the pressure

Come play my game, I’ll test ya

Psychosomatic, addict, insane

Breathe the pressure

Come play my game, I’ll test ya

Psychosomatic, addict, insane

Come play my game

Inhale, inhale, you’re the victim

Come play my game

Exhale, exhale, exhale”

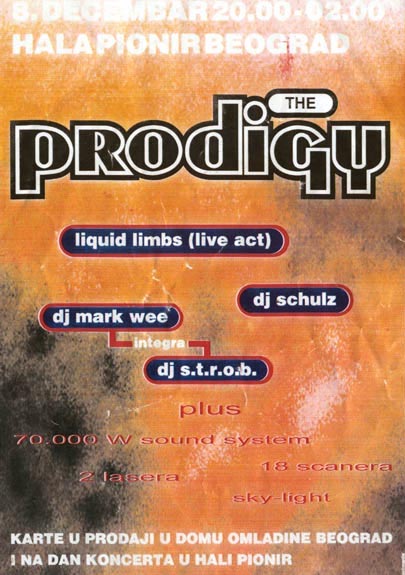

The Prodigy – Breathe, 1995

On 8th December, 1995 The Prodigy premiered their track Breathe in the Pionir Hall in Belgrade, Serbia. It was the last week of the Bosnian War, and it was a controversial decision for the UK band to play a concert in the country of the aggressor amidst international sanctions. Ever since I saw the video of this concert, the song for me carried an added intensity and violence. The setting for a band testing the boundaries of club music and sonic transgression.

“When I was younger I thought

That to kill or be killed

Was a thing to be proud of

Victim of change

Prisoner of hope, hanged by the neck

On the end of a rope

I don’t know… I don’t care…”

Bruce Dickinson (Iron Maiden) – Gods of War, 1994

One year earlier, in December 1994, Bruce Dickinson of the heavy metal band Iron Maiden had played a concert with his band Skunkworks in the Bosnian Cultural Center in the besieged city of Sarajevo. Photographer Milomir Kovačević Strašni remembers: “The concert passed in a sort of haze. That’s why I probably took so many photos. I surely wouldn’t have used seven rolls of film had it not been for the energy and the madness. I might have used my last seven rolls. The entire atmosphere with the audience and all that took me back to different times, to a life I lived before and the things I did before the war.” (Source: documentary Scream for me Sarajevo, 2016)

“V̶L̶A̶D̶I̶M̶I̶R̶ VOLODYMYR

He didn’t say for sure he’d come.”

Samuel Beckett – Waiting for Godot, 1952

One year before that concert, in August 1993, Susan Sontag had staged Beckett’s Waiting for Godot at the Sarajevo Youth Theater. As her biographer Benjamin Moser writes “This performance was produced without so much as electricity, and without costumes worthy of the name, and with a set made of nothing more than the plastic sheets the United Nations distributed to cover windows shot out by sniper fire.” While she tried to bring international attention to the situation of the people in Sarajevo, her engagement was also met with criticism. Jean Baudrillard wrote in his text No Pity for Sarajevo: “Recently Susan Sontag came to direct Waiting for Godot in Sarajevo. […] what is worst is not this extra portion of cultural soul. It is, rather, the condescension and error of judgement with regard to force and weakness. It is they who are strong, it is we who are weak – and who go searching in their lands for what it takes to regenerate our weakness and our loss of reality.”

“For Peace. Against War. Who is not?

But how can you stop those bent on genocide without making war?”

Susan Sontag, 1999

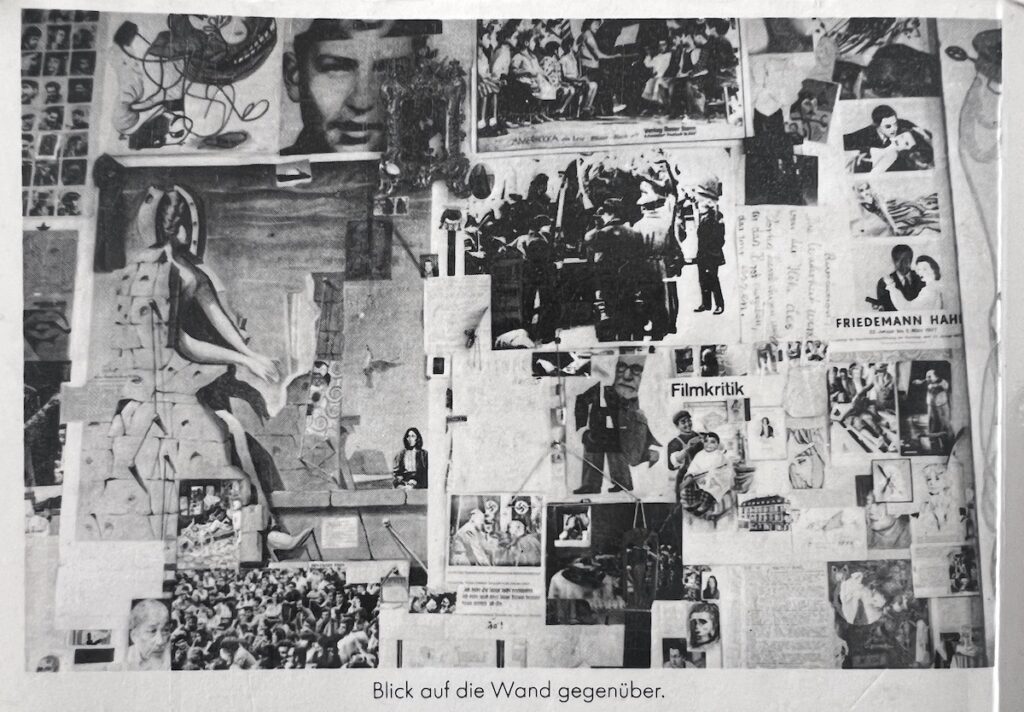

Philosopher Boris Buden quotes Baudrillard’s critique of Sontag in his essay Field Trip to Reality from 1997. His book Zone of Transition – Of the End of Post-Communism, published 2009, 20 years after the fall of the Berlin Wall, became an essential work for artists, curators and left thinkers in the former “Eastern Bloc”, including Ukraine. Ukrainians thus were deeply irritated by his text The West at War, published on e-flux in April 2022 – as a reaction to Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine. Since the only hopeful part of the text, the final part, in which Buden sees his vision for the end of the Ukrainian war in the revolution within Russia, was misunderstood by many, Buden referred to this part of the text in a panel discussion in Berlin in September 2023 and clarified that he had meant a “communist world revolution” as a solution to the situation. This statement left the Ukrainian audience perplexed. The disregard for the living conditions of Ukrainians, their needs and demands, shows how irresponsible it is to compare the conclusions of the Yugoslav wars with the war in Ukraine. In this logic, all the demands of Ukrainians for national sovereignty and respect for its borders to protect its citizens should therefore not be taken into consideration, as they are based on national law. But it is all the more important to listen to the current voices that are now coming from the war zone.

“We need to understand and combat fascism not because so many fell victim to it, not because it stands in the way of the triumph of socialism, not even because it might “return again,” but primarily because, as a form of reality production that is constantly present and possible under determinate conditions, it can, and does, become our production.”

Klaus Theweleit – Male Phantasies, 1987

Klaus Theweleit’s book Male Phantasies from 1987 can be considered as one of the standard works on the prehistory of National Socialism. The book centers upon the fantasies of a group of men who played a crucial role in the rise of Nazism. His perspective on the ideology that shaped the men responsible for the atrocities of WWII gave me insight in understanding the roots of fascism in Germany as well as how these structures live on until today. I respect his writing and thinking tremendously, so I was shocked about his statements regarding russia’s war on Ukraine. “When people cry out for weapons, what I hear first and foremost is: they are destroying internal social freedoms in our country. In any case, they are on their way.” (Klaus Theweleit in conversation with Jakob Augstein, 2023). Where he refuses to see and understand the situation the Ukrainians are in, who want to live in peace, free and self-determined. That the pacifist demands for Ukraine to surrender to the aggressor in a genocidal war enforces the power dynamics he described in Male Phantasies. I have taken the freedom of quoting Theweleit himself, from his book on colonialism, which, when put in the context of Russia’s imperial war, can open our eyes to the difficulties of demanding pacifism from the victims in a war:

“What chance do I have of being a pacifist if all the cultural techniques through which I breathe, perceive, think, produce, through which I love and live are themselves violence, if my peacefulness itself includes violence?”

Klaus Theweleit – HON, 2020

When I got the invitation to participate in this year’s Kyiv Biennial, I was thinking about The Prodigy, Susan Sontag and Iron Maiden, and their reasons for doing art in the context of war. What is my reason for coming to Ukraine? Can a Biennial contribute to people surviving in a new state of normality in a war zone? And outside of Ukraine, will it bring empathy back to not see the same destruction every day but people longing to live in peace? Am I looking to regain a sense of reality? Or is it that speaking about “East” and “West” and what that means I can no longer explore from the perspective of Germany, but need to discuss it at the current crystallization point of this question, in Ukraine?

I take this as a starting point for the project OSTBLOCK that has been in the making with ifa (Institut für Auslandsbeziehungen) since 2021. Over the course of several years, I will travel to countries that had diplomatic relations to the former socialist East-Germany (DDR) and where artist exchanges took place. I see my practice in the tradition of these artistic relations, spanning the former socialist world. Today, in a situation that can no longer be called “post-socialist” and where cold and hot wars force us to rethink the global order, I want to look at the role that history, art history and artists play in shaping ideas for different futures. Taking the complex legacy of whatever that “Ostblock” was and turning it into a future machine.

Henrike Naumann

Ivano-Frankivsk, Ukraine, 3rd October 2023

Go to home