Ostalgie

KOW Berlin, 2019

Karl-Marx-Monument Chemnitz, 2019

Tretyakov Gallery Moscow, 2021

Ludwigforum Aachen, 2023

Harvard Art Museums, 2024

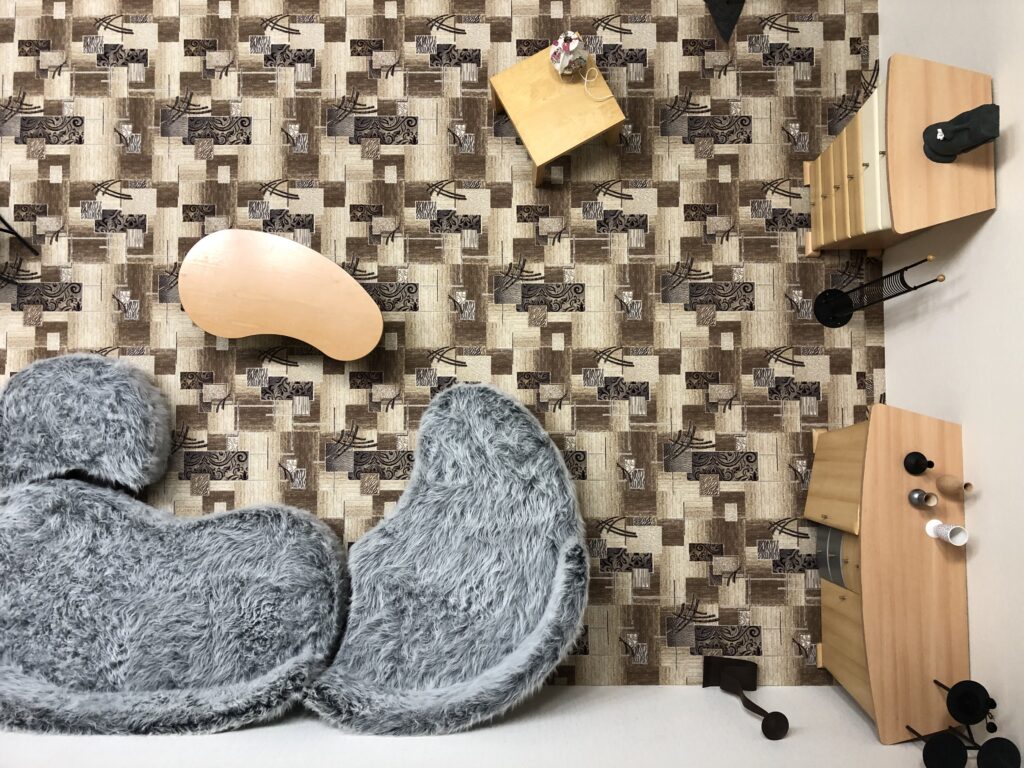

Henrike Naumann’s first exhibition at KOW was about history in the broadest sense of the term. More precisely, it was a reflection on memory and the mechanisms through which recent history is written by still more recent history, as well as a study of the ways in which the now defunct German Democratic Republic figured in collective East German memory during the 1990s. The exhibition’s title was the portmanteau word Ostalgie—a contraction of the German words for east and nostalgia—which has come to describe nostalgia for everyday life in East Germany before it was exposed to the hardships of capitalism. Needless to say, this nostalgia is not only a highly selective retrospective construction but it also has been given its own capitalist inflection, marketed through GDR memorabilia and club nights.

Dominikus Müller: Henrike Nauman KOW, Translated by Nathaniel McBride, in: Artforum, 05/2019

Henrike Naumann’s first solo exhibition at KOW, which at the same time marks the gallery’s farewell to its rooms at Brunnenstraße 9 after ten years, is dedicated to the historical dimensions of a particular manifestation of nostalgia: Ostalgie. The exhibition space itself already contains a nostalgic gesture: the gap in the building preserved in Arno Brandlhuber’s architecture, which can still be visited on Google Street View and from which KOW’s gallery space emerged in 2009, refers to a Berlin-Mitte that has perished. The adjacent building, cynically described by a multimillionaire on the occasion of the 20th anniversary of the fall of the Berlin Wall with the saying “This house used to stand in another country,” marks an almost hostile appropriation of memory.

Ostalgia can be seen as an individual and collective feeling of longing: as a positively perceived projection of a fictitious GDR society composed of media discourses and selective fragments of memory. This feeling is at odds with the communist philosophy of history of historical materialism. In the logic of the lawful progress of history, the past could not possibly be better than the future. However, with the collapse of communism, global-authoritarian roll-back, and global warming, the future has lost its appeal as a social design. On the other hand, Ostalgie is also a form of resistance, a counter-memory (,Counter Memory’, Daphne Berdahl) that opposes a hegemonic culture of remembrance and commemoration as well as a colonization of East German lifeworlds.

The linear staircase model of Marxist social development and the capitalist growth paradigm share a positive point of reference: the primal society of gatherers and hunters as a projection of the human foundations of the social. Naumann’s installation Ostalgie (Urgesellschaft), on the first floor of the gallery, takes a close look at the materiality of anthropological narratives and reactionary social designs. Everyday GDR objects mingle with cartoonesque furniture to create a flintstone-like ,Neo-Stone Age’ (Markues).

Naumann’s work questions the appeal of utopias whose promise lies in reducing the complexity of the present and constructing a supposedly simple past. Gender, racial, social orders, clearly enforced with violence and power, form the mental constants of this imagined ,retrotopia’ (Zygmunt Bauman). When the ground no longer supports, it becomes a wall.

Mass unemployment, devaluation of life achievements, flexibilization and dissolution of social ties were the landmarks of an East Germany perceived as a jungle, for the mapping of which West German civil servants received a special payment until 1995, the so-called bush allowance. It was only in this ,land before our time’ (Littlefoot) that the ,East Germans’ established themselves as an attribution of themselves and others. Ostalgic feelings, products, and practices are ideational and material expressions of the active production of cultural difference. Clemens Villinger

The exhibition’s reflexive approach—examining past forms of historical narrative in a manner that is itself historicizing—is already nascent in Naumann’s material of choice: cheap ’90s copies of postmodern designs from the ’80s, which themselves once aspired to ironically recycle history. Already outdated on arrival, these symbols of a bright capitalist future flooded East German living rooms after 1990. But in the late 2010s, all those curved mirrors, cheap veneered furniture pieces, and quixotically contorted wall units add up to a rather bleak and dreary landscape of memory.

Dominikus Müller: Henrike Nauman KOW, Translated by Nathaniel McBride, in: Artforum, 05/2019

Go to homeHer art seems both anachronistic and timely. The autonomy of the art world is a privilege, the isolation of left-behind communities is not.

Philipp Hindahl: Social Ruins of Post-Unification: Henrike Naumann, in: Mousse Magazine 70/2020